§ Key Event Receipt Infrastructure (KERI)

Specification Status: v1.0 Draft

Latest Draft:

https://github.com/trustoverip/tswg-keri-specification

Author:

Editors:

Contributors:

- Participate:

- GitHub repo

- Commit history

§ Foreword

This publicly available specification was approved by the ToIP Foundation Steering Committee on [dd month yyyy] must match date in subtitle above]. The ToIP permalink for this document is:

[permalink for this deliverable: see instructions on this [wiki page](https://wiki.trustoverip.org/display/HOME/File+Names+and+Permalinks)]

The mission of the Trust over IP (ToIP) Foundation is to define a complete architecture for Internet-scale digital trust that combines cryptographic assurance at the machine layer with human accountability at the business, legal, and social layers. Founded in May 2020 as a non-profit hosted by the Linux Foundation, the ToIP Foundation has over 400 organizational and 100 individual members from around the world.

Any trade name used in this document is information given for the convenience of users and does not constitute an endorsement.

This document was prepared by the ToIP Technical Stack Working Group.

Any feedback or questions on this document should be directed to https://github.com/trustoverip/tswg-keri-specification/issues

THESE MATERIALS ARE PROVIDED “AS IS.” The Trust Over IP Foundation, established as the Joint Development Foundation Projects, LLC, Trust Over IP Foundation Series (“ToIP”), and its members and contributors (each of ToIP, its members and contributors, a “ToIP Party”) expressly disclaim any warranties (express, implied, or otherwise), including implied warranties of merchantability, non-infringement, fitness for a particular purpose, or title, related to the materials. The entire risk as to implementing or otherwise using the materials is assumed by the implementer and user. IN NO EVENT WILL ANY ToIP PARTY BE LIABLE TO ANY OTHER PARTY FOR LOST PROFITS OR ANY FORM OF INDIRECT, SPECIAL, INCIDENTAL, OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES OF ANY CHARACTER FROM ANY CAUSES OF ACTION OF ANY KIND WITH RESPECT TO THESE MATERIALS, ANY DELIVERABLE OR THE ToIP GOVERNING AGREEMENT, WHETHER BASED ON BREACH OF CONTRACT, TORT (INCLUDING NEGLIGENCE), OR OTHERWISE, AND WHETHER OR NOT THE OTHER PARTY HAS BEEN ADVISED OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGE.

§ Introduction

The original design of the Internet Protocol (IP) has no security layer(s) [RFC0791], providing no built-in mechanism for secure attribution to the source of an IP packet. Anyone can forge an IP packet, and a recipient may not be able to ascertain when or if the packet was sent by an imposter. This means that secure attribution mechanisms for the Internet must be overlaid. This documents presents an identifier system security overlay, called the Key Event Receipt Infrastructure (KERI) protocol, that serves as a trust spanning layer for the Internet. This overlay includes a primary root-of-trust in a Self-certifying identifier (SCID) that provides a formalism for Autonomic identifiers (AIDs), Autonomic namespaces (ANs), and the basis for a universal Autonomic Identity System (AIS).

The KERI protocol provides verifiable authorship (authenticity) of any message or data item via secure cryptographically verifiable attribution to a SCID as a primary root-of-trust [[4]] [[16]] [[18]] [[19]] [[17]] [[15]]. This root-of-trust is cryptographic, not administrative, because it does not rely on any trusted third-party administrative process but may be established with cryptographically verifiable data structures. This cryptographic root-of-trust enables end verifiability where every data item may be cryptographically attributable to its source by any recipient verifier, without reliance on any infrastructure not under the verifier’s ultimate control. Therefore, KERI has no security dependency on any other infrastructure and does not rely on security guarantees that may or may not be provided by the traditional internet infrastructure. This makes intervening operational infrastructure replaceable, enabling ambient verifiability (verification by anyone, anywhere, at any time).

A SCID is strongly bound at inception to a cryptographic keypair that is self-contained unless control over the SCID needs to be transferred to a new keypair. The KERI protocol provides end-verifiable control provenance over a variant of SCID, called an Autonomic identifier (AID), via signed transfer statements in an append-only chained Key event log (KEL). The key management operation for tansferring control over an AID is implemented via a novel key pre-rotation scheme [[6]]. With pre-rotation, control over an AID can be re-established by rotating to a one-time use set of unexposed but pre-committed rotation keypairs. This approach fixes the foundational flaw in traditional Public key infrastructure (PKI), which is insecure key rotation. KERI enables decentralized public key infrastructure (DPKI) that is more secure and more portable. KERI may be viewed as a viable reboot of the Web-of-Trust concept for DPKI because KERI fixes the hard problem of DPKI, which is key rotation.

Two primary trust modalities motivated the design of the KERI protocol, namely a direct (one-to-one) mode and an indirect (one-to-any) mode. In the direct mode, two entities establish trust over AIDs via a direct exchange of their counterparts’ verified signatures. In the indirect mode, trust over AIDs depends on witnessed Key event receipt logs (KERLs) as a secondary root-of-trust for validating key events. The security and accountability guarantees of indirect mode are provided by KERI’s Algorithm for Witness Agreement (KAWA) among a set of key event Witnesses. The KAWA approach may be much more performant and scalable than more complex approaches that depend on a total ordering distributed consensus ledger. Nevertheless, KERI may employ a distributed consensus ledger when other considerations make it the best choice.

The KERI approach to Decentralized key management infrastructure (DKMI) allows for more granular composition. Moreover, because KERI is event streamed, it enables DKMI to operate in-stride with data events streaming applications such as web 3.0, IoT, and others where performance and scalability are more important. The core KERI engine is independent of identifier namespace. This makes KERI a candidate for a universal portable DKMI. This system uses the design principle of minimally sufficient means for appropriate levels of security, performance, and adoptability to be a viable candidate as the DKMI that underpins a trust-spanning layer for the Internet.

§ Scope

Implementation design of a protocol-based decentralized key management infrastructure that enables secure attribution of data to a cryptographically derived identifier with strong (cryptographically verifiable) bindings between each of the identifier, a set of asymmetric signing key pairs that are the key state, a controlling entity that holds the private keys, and a cryptographically verifiable data structure that enables changes to that key state. Thus, security over secure attribution is reduced to key management. This key management includes, for the first time, a practical solution to the hard problem of public key rotation. There is no reliance on trusted third parties. The resulting secure attribution is fully end-to-end verifiable.

Because of the reliance on asymmetric (public, private) digital signing key pairs, this may be viewed as a type of decentralized public key infrastructure (DPKI). The protocol supports cryptographic agility for both pre- and post-quantum attack resistance. The application scope includes any electronically transmitted information. The implementation dependency scope assumes no more than cryptographic libraries that provide cryptographic strength pseudo-random number generators, cryptographic strength digest algorithms, and cryptographic strength digital signature algorithms.

§ Normative references

The following documents are referred to in the text in such a way that some or all of their content constitutes requirements of this document. For dated references, only the edition cited applies. For undated references, the latest edition of the referenced document (including any amendments) applies.

- ISO/IEC 7498-1:1994 Information technology — Open Systems Interconnection — Basic Reference Model: The Basic Model. June 1999. Introduction. Retrieved 26 August 2022.

[a]. IETF RFC-2119 Key words for use in RFCs to Indicate Requirement Levels [a]: https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc2119.txt

[b]. IETF RFC-4648 Base64 [b]: https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc4648.txt

[c]. IETF RFC-3339 DateTime [c]: https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc3339.txt

§ Terms and Definitions

For the purposes of this document, the following terms and definitions apply.

ISO and IEC maintain terminological databases for use in standardization at the following addresses:

- ISO Online browsing platform: available at https://www.iso.org/obp

- IEC Electropedia: available at http://www.electropedia.org/

- Authentic Chained Data Container

- a directed acyclic graph with properties to provide a verifiable chain of proof-of-authorship. See the full specification

- Autonomic identifier

- a self-managing cryptonymous identifier that must be self-certifying (self-authenticating) and must be encoded in CESR as a qualified Cryptographic primitive.

- Autonomic identity system

- an identity system that includes a primary root-of-trust in self-certifying identifiers that are strongly bound at issuance to a cryptographic signing (public, private) key pair. An AIS enables any entity to establish control over an AN in an independent, interoperable, and portable way.

- Autonomic namespace

- a namespace that is self-certifying and hence self-administrating. An AN has a self-certifying prefix that provides cryptographic verification of root control authority over its namespace. All derived AIDs in the same AN share the same root-of-trust, source-of-truth, and locus-of-control (RSL). The governance of the namespace is therefore unified into one entity, that is, the controller who is/holds the root authority over the namespace.

- Backer

- an alternative to a traditional KERI based Witness commonly using Distributed Ledger Technology (DLT) to store the KEL for an identifier.

- Concise Binary Object Representation

- a binary serialization format, similar in concept to JSON but aiming for greater conciseness. Defined in [RFC7049].

- Configuration traits

- a list of specially defined strings representing a configuration of a KEL. See (Configuration traits field)[#configuration-traits-field].

- Controller

- an entity that can cryptographically prove the control authority over an AID and make changes on the associated KEL. A controller of a multi-sig AID may consist of multiple controlling entities.

- Cryptographic Primitive

- the serialization of a value associated with a cryptographic operation including but not limited to a digest (hash), a salt, a seed, a private key, a public key, or a signature.

- Cryptonym

- a cryptographic pseudonymous identifier represented by a string of characters derived from a random or pseudo-random secret seed or salt via a one-way cryptographic function with a sufficiently high degree of cryptographic strength (e.g., 128 bits, see appendix on cryptographic strength) [[13]] [[14]] [[12]] [[11]]. A Cryptonym is a type of Primitive. Due to the entropy in its derivation, a Cyptonym is a universally unique identifier and only the Controller of the secret salt or seed from which the Cryptonym is derived may prove control over the Cryptonym. Therefore the derivation function must be associated with the Cryptonym and may be encoded as part of the Cryptonym itself.

- Current threshold

- represents the number or fractional weights of signatures from the given set of current keys required to be attached to a Message for the Message to be considered fully signed.

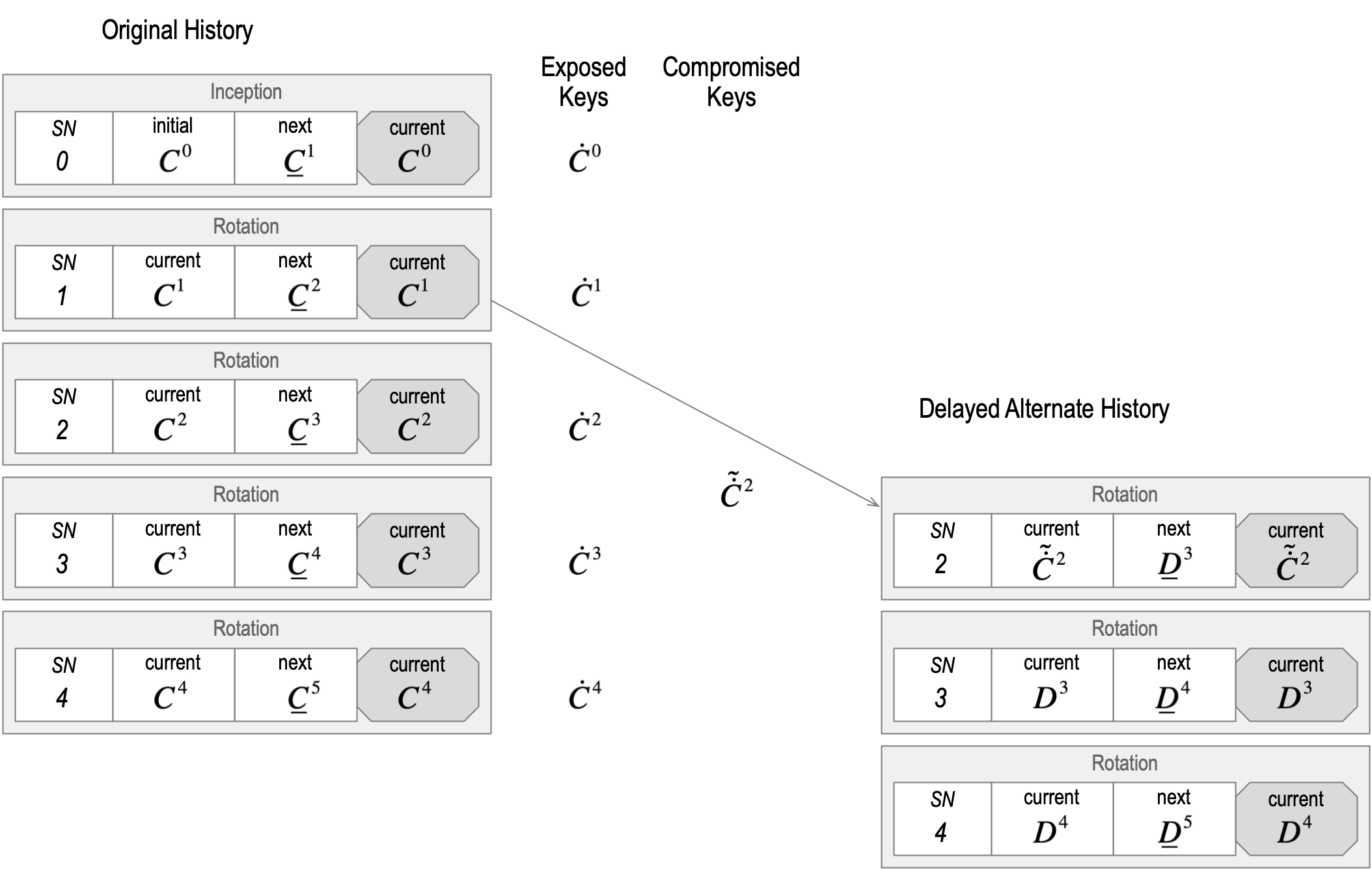

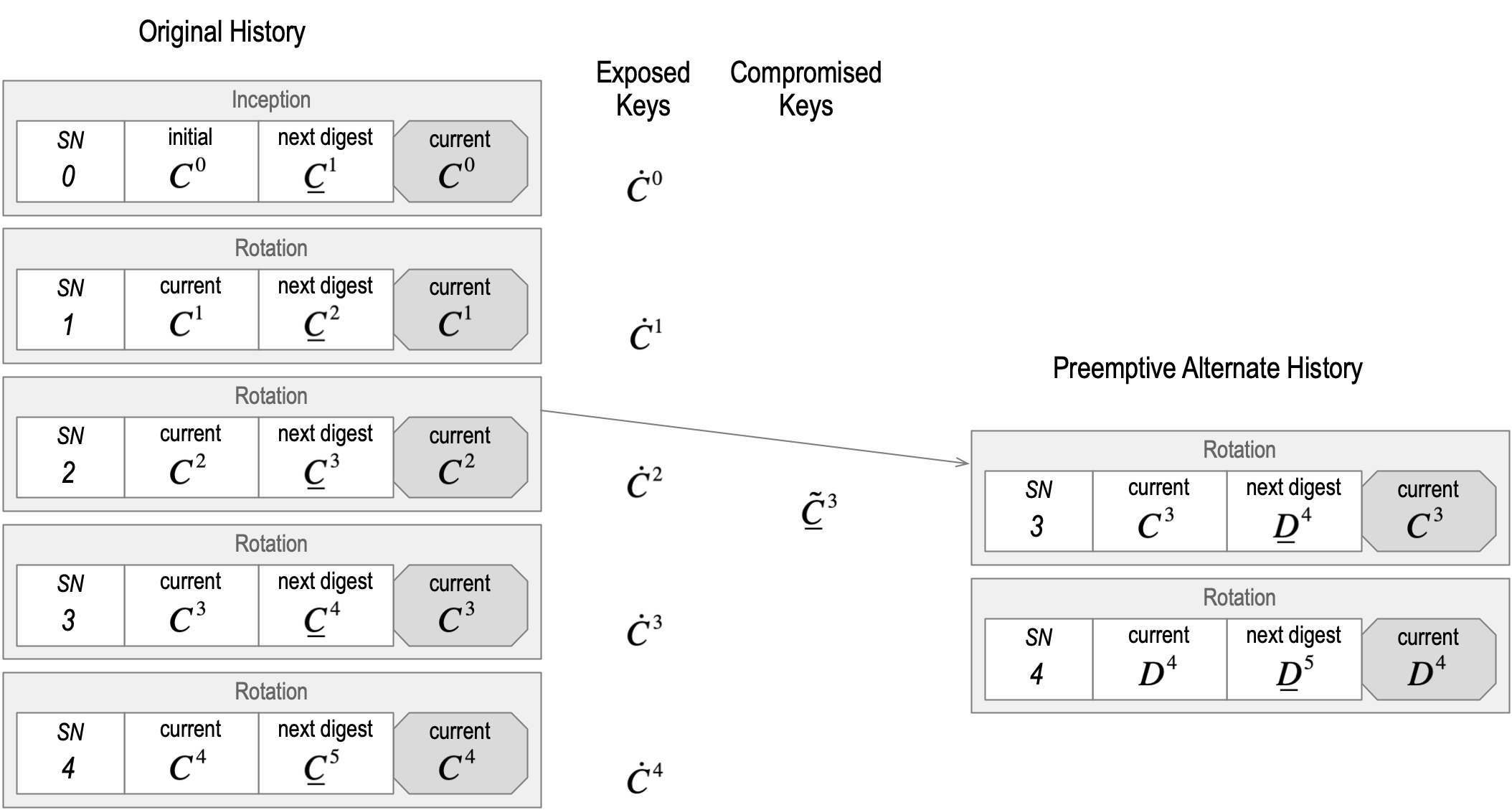

- Dead-Attack

- an attack on an establishment event that occurs after the Key-state for that event has become stale because a later establishment event has rotated the sets of signing and pre-rotated keys to new sets. See (Security Properties of Prerotation)[#dead-attacks].

- Decentralized key management infrastructure

- a key management infrastructure that does not rely on a single entity for the integrity and security of the system as a whole. Trust in a DKMI is decentralized through the use of technologies that make it possible for geographically and politically disparate entities to reach an agreement on the key state of an identifier DPKI.

- Duplicity

- the existence of more than one Version of a Verifiable KEL for a given AID.

- End-verifiability

- a data item or statement may be cryptographically securely attributable to its source (party at the source end) by any recipient verifier (party at the destination end) without reliance on any infrastructure not under the verifier’s ultimate control.

- Establishment event

- a Key event that establishes or changes the Key state which includes the current set of authoritative keypairs (Key state) for an AID.

- First-Seen

- refers to the first instance of a Message received by any Witness or Watcher. The first-seen event is always seen, and can never be unseen. It forms the basis for Duplicity detection in KERI based systems.

- Inception

- the operation of creating an AID by binding it to the initial set of authoritative keypairs and any other associated information. This operation is made verifiable and Duplicity evident upon acceptance as the Inception event that begins the AID’s KEL.

- Inception event

- an Establishment event that provides the incepting information needed to derive an AID and establish its initial Key state.

- Interaction event

- a Non-establishment event that anchors external data to the Key state as established by the most recent prior Establishment event.

- KERI’s Algorithm for Witness Agreement

- a type of Byzantine Fault Tolerant (BFT) algorithm

- Key event

- concretely, the serialized data structure of an entry in the Key event log (KEL) for an AID. Abstractly, the data structure itself. Key events come in different types and are used primarily to establish or change the authoritative set of keypairs and/or anchor other data to the authoritative set of keypairs at the point in the KEL actualized by a particular entry.

- Key event log

- a Verifiable data structure that is a backward and forward chained, signed, append-only log of key events for an AID. The first entry in a KEL must be the one and only Inception event of that AID.

- Key event message

- message whose body is a Key event and whose attachments may include signatures on its body.

- Key event receipt

- message whose body references a Key event and whose attachments must include one or more signatures on that Key event.

- Key event receipt log

- a key event receipt log is a KEL that also includes all the consistent key event receipt Messages created by the associated set of witnesses. See annex Key event receipt log

- Key-State

- a set of authoritative keys for an AID along with other essential information necessary to establish, evolve, verify, and validate control-signing authority for that AID. This information includes the current public keys and their thresholds (for a multi-signature scheme); pre-rotated key digests and their thresholds; witnesses and their thresholds; and configurations. An AID’s key state is first established through its inception event and may evolve via subsequent rotation events. Thus, an AID’s key state is time-dependent.

- Live-Attack

- an attack that compromises either the current signing keys used to sign non-establishment events or the current pre-rotated keys needed to sign a subsequent establishment event. See (Security Properties of Prerotation)[#live-attacks].

- Message

- a serialized data structure that comprises its body and a set of serialized data structures that are its attachments. Attachments may include but are not limited to signatures on the body.

- Next threshold

- represents the number or fractional weights of signatures from the given set of next keys required to be attached to a Message for the Message to be considered fully signed.

- Non-establishment event

- a Key event that does not change the current Key state for an AID. Typically, the purpose of a Non-establishment event is to anchor external data to a given Key state as established by the most recent prior Establishment event for an AID.

- Primitive:

- a serialization of a unitary value. All Primitives in KERI must be expressed in CESR [[1]].

- Rotation

- the operation of revoking and replacing the set of authoritative keypairs for an AID. This operation is made verifiable and Duplicity evident upon acceptance as a Rotation event that is appended to the AID’s KEL.

- Rotation event

- an Establishment Event that provides the information needed to change the Key state which includes a change to the set of authoritative keypairs for an AID.

- Salt

- random data fed as an additional input to a one-way function that hashes data.

- Seal

- a seal is a cryptographic commitment in the form of a cryptographic digest or hash tree root (Merkle root) that anchors arbitrary data or a tree of hashes of arbitrary data to a particular event in the key event sequence. See annex (Seal)[#seal].

- Self-addressed data

- a representation of data content from which a SAID is derived. The SAID is both cryptographically bound to (content-addressable) and encapsulated by (self-referential) its SAD SAID.

- Self-addressing identifiers

- an identifier that is content-addressable and self-referential. A SAID is uniquely and cryptographically bound to a serialization of data that includes the SAID as a component in that serialization SAID.

- Self-certifying identifier

- a type of Cryptonym that is uniquely cryptographically derived from the public key of an asymmetric signing keypair,

(public, private). - Validator

- any entity or agent that evaluates whether or not a given signed statement as attributed to an identifier is valid at the time of its issuance.

- Verifiable

- a condition of a KEL: being internally consistent with integrity of its backward and forward chaining digest as well as authenticity of its non-repudiable signatures.

- Verifier

- any entity or agent that cryptographically verifies the signature(s) and digests on an event Message.

- Version

- an instance of a KEL for an AID in which at least one event is unique between two instances of the KEL

- Watcher

- an entity or component that keeps a copy of a KERL for an identifier but that is not designated by the controller of the identifier as one of its witnesses. See annex watcher

- Witness

- a witness is an entity or component designated (trusted) by the controller of an identifier. The primary role of a witness is to verify, sign, and keep events associated with an identifier. A witness is the controller of its own self-referential identifier which may or may not be the same as the identifier to which it is a witness. See Annex A under KAWA (KERI’s Algorithm for Witness Agreement).

§ KERI foundational overview

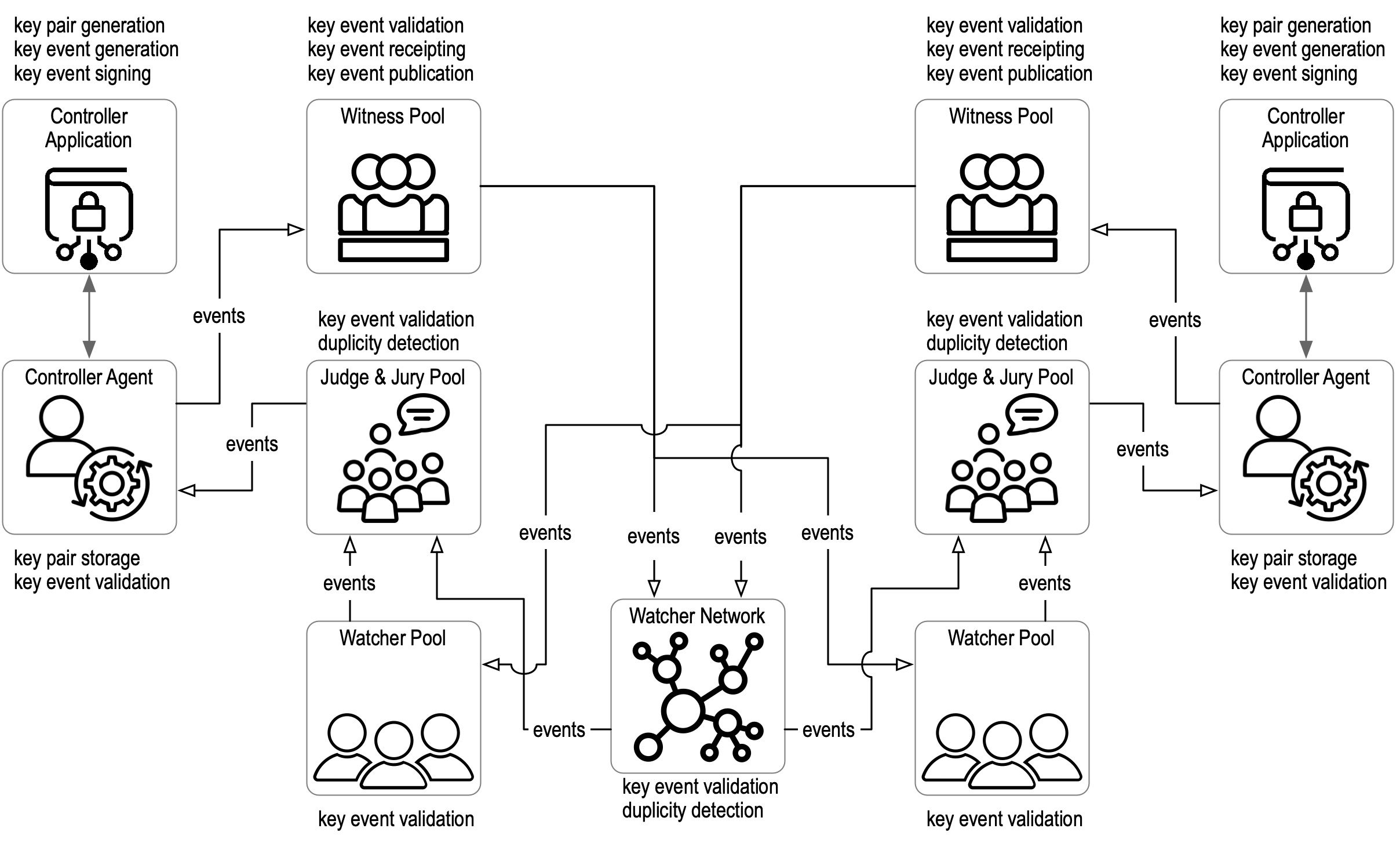

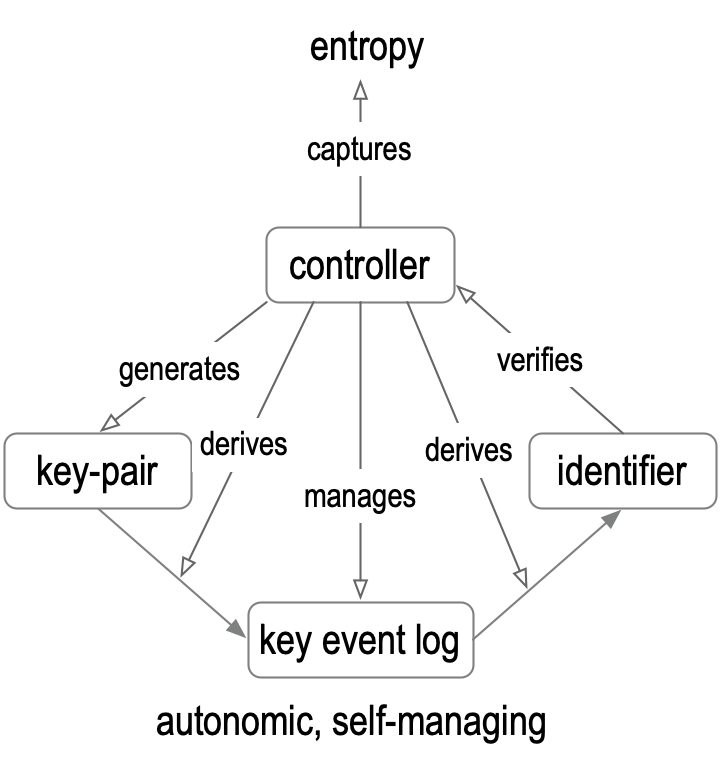

§ Infrastructure and ecosystem overview

This section provides a high-level overview of the infrastructure components of a live KERI ecosystem and how they interact. It does not provide any low-level details and only describes the components superficially. However, it should help understand how all the parts fit together as one reads through the more detailed sections.

§ Controller Application

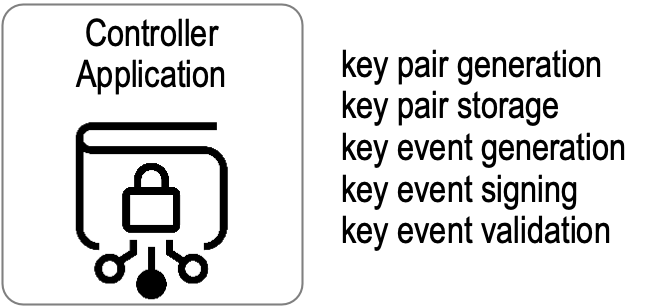

Each KERI AID is controlled by an entity (or entities when multi-sig) that holds the digital signing private keys belonging to the current authoritative key state of the AID. This set of entities is called the AID controller, or Controller for short. Each controller has an application or suite or applications called the controller application or application for short. The controller application provides five functions with respect to the digital signing key pairs that control the controller’s AID. These five functions manage the associated key state via key events. These functions are:

- key pair generation,

- key pair storage,

- key event generation,

- key event signing, and

- key event validation.

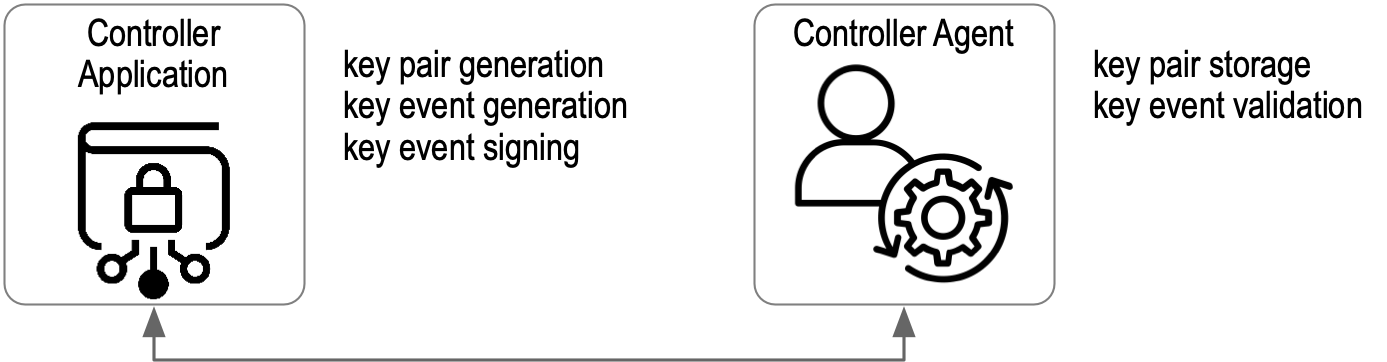

Key event validation includes everything needed to validate events, including structure validation, chaining digest verification, signature verification, and witness receipt verification. The execution of these functions, including the associated code and data, SHOULD be protected by the controller using best practices. For example, this might be accomplished by securely installing the controller application on a device in the physical possession of the controller, such as a mobile phone with appropriate secure storage and trusted code execution environments. Alternatively, the functions might be split between devices where a remote software agent that runs on behalf of the controller MAY host encrypted keypair storage and highly available key event validation functions while the more critical keypair generation, key event generation, and key event signing functions are on a device in the user’s possession. The latter might be called a key chain or wallet. The extra security and scalability properties of delegated AIDs enable other arrangements for securely hosting the five functions. For the sake of clarity and without loss of generality, the controller application, including any devices or software agents, will be referred to as the controller application or application for short.

Figure: Controller Application Functions

Figure: Controller Application with Agent

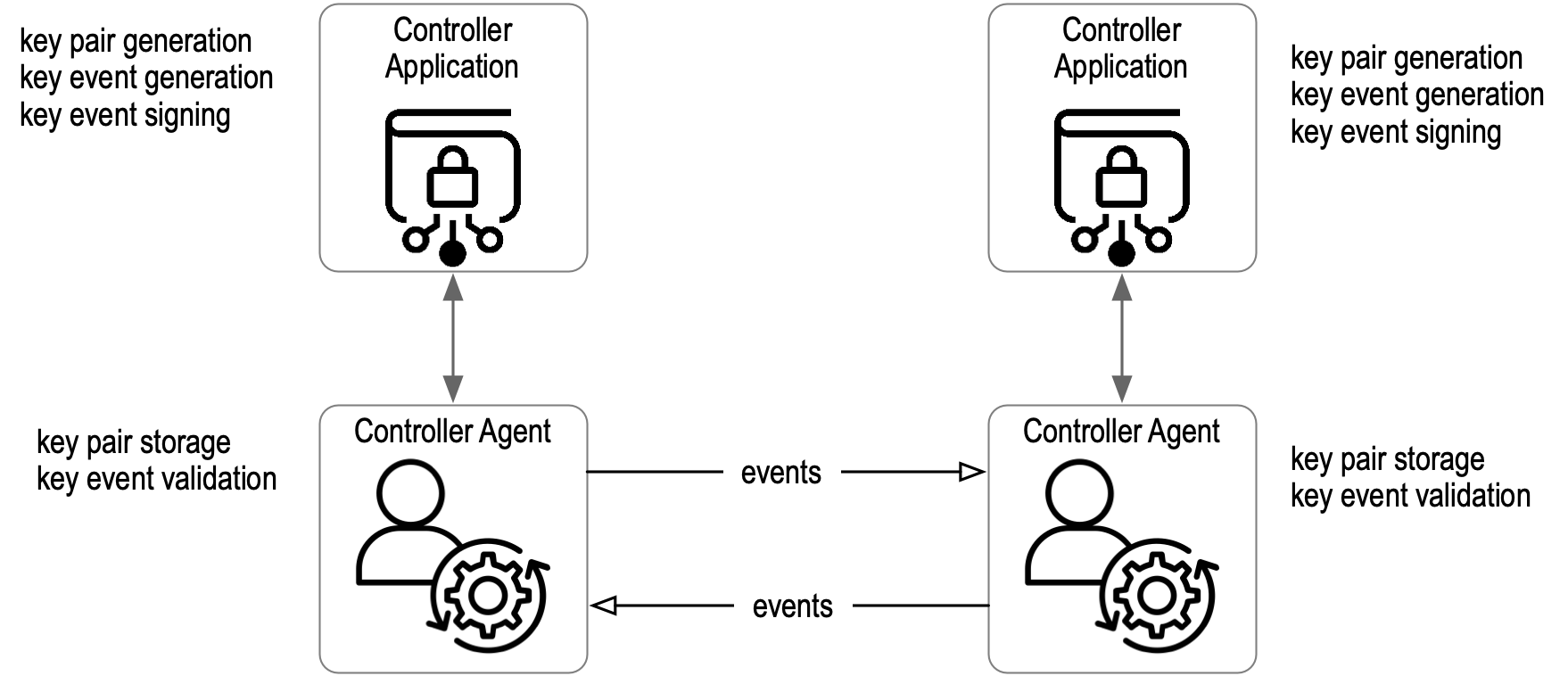

§ Direct exchange

The simplest mode of operation is that a pair of controllers, each with their own AID, use their respective applications (including agents when applicable) to directly exchange key event messages that verifiably establish the current key state of their own AID with the other controller. For each exchange of key events, the destination controller acts as a validator of events received from the source controller. Therefore, given any key event, a given entity is either the event’s controller or a validator of some other controller’s event.

The set of key event messages forms an append-only, cryptographically verifiable data structure called a key event log or KEL. The events in a KEL are signed and are both forward and backward-chained. The backward chaining commitments are cryptographic digests of the previous event. The forward chaining commitments are cryptographic digests of the next set of public keys that will constitute the key state after a key rotation. The commitments are nonrepudiably signed with the private keys of the current key state. Each KEL is somewhat like a “blockchain” that manages the key state for one and only one AID. In addition to key states, each KEL also manages commitments to external data. These commitments are signed cryptographic digests of external data called seals. When included in a KEL, a seal binds (or anchors) the external data to the key state of the AID at the location in the KEL where the seal appears. This binding enables a controller to make cryptographically verifiable, non-repudiable issuances of external data that are bound to a specific key state of that AID.

By exchanging KELs, each controller can validate the current key state of the other and, therefore, securely attribute (authenticate) any signed statements or any sealed issuances of data. This bootstraps the use of authentic data in any interaction or transaction between the pair of controllers. This is the mission of KERI.

Figure: Direct Exchange

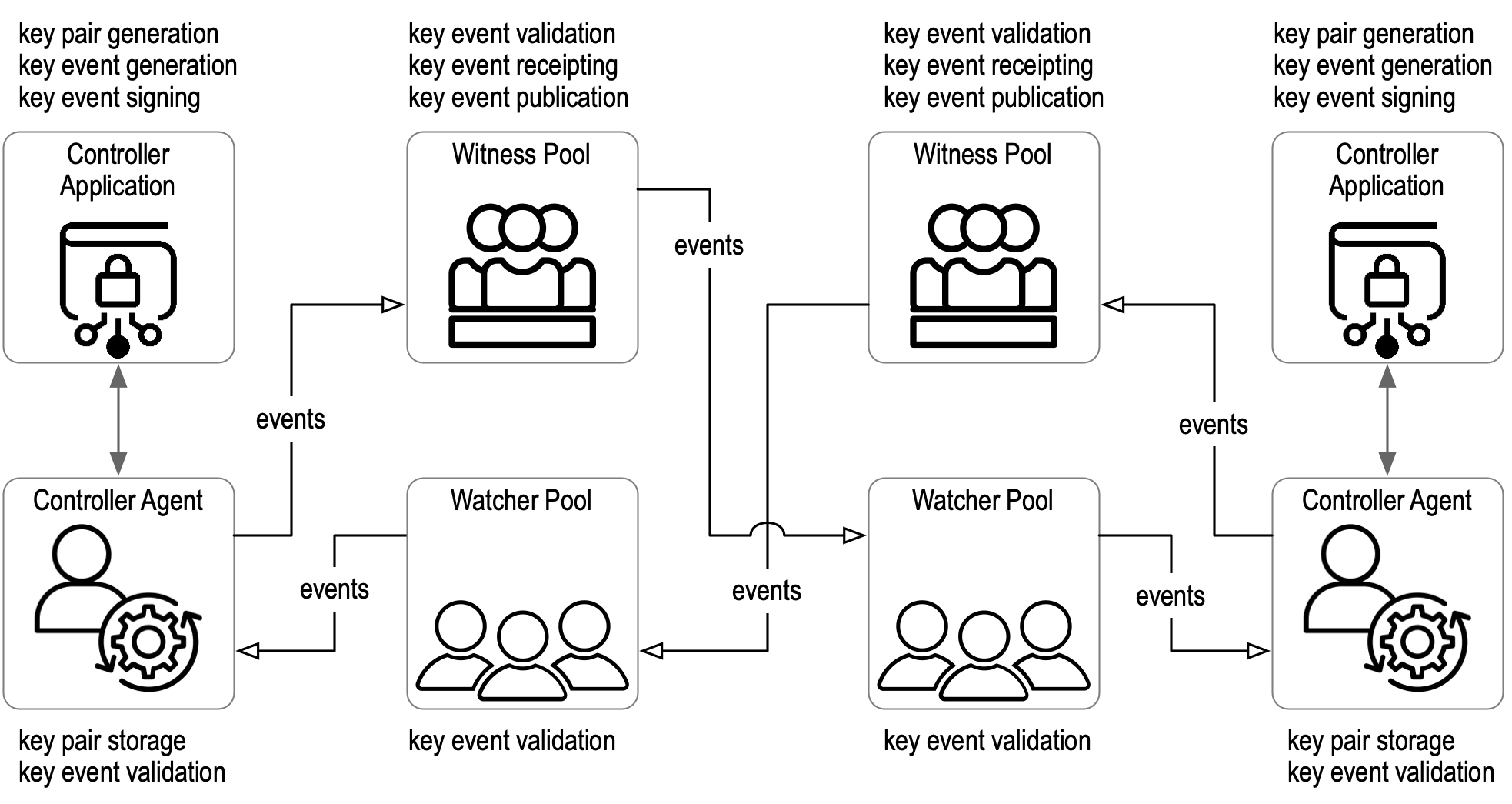

§ Indirect exchange via witnesses and watchers

For many if not most use cases, the direct exchange of key event messages between controller applications (including agents when applicable) may not provide sufficient availability, scalability, or even security. KERI includes two other components for those use cases. These components are witnesses and watchers.

Each controller of an AID MAY create or choose to use a set or pool of witnesses for that AID. The controller chooses how the witnesses are hosted. It MAY use a witness service provided by some other party or MAY directly host its own witnesses in its own infrastructure or some combination of the two. Regardless, the composition of the Witness pool is under the ultimate control of the AID’s controller, which means the controller MAY change the witness infrastructure at will. Witnesses for the AID are managed by the key events in the AID’s KEL. Each witness creates a signed receipt of each event it witnesses, which is exchanged with the other witnesses (directly or indirectly). Based on those receipts, the witness pool uses an agreement algorithm called KAWA that provides high availability, fault tolerance, and security guarantees. Thereby, an AID’s witness pool constitutes a highly available and secure promulgation network for that AID.

Likewise, each controller acting as a validator of some other controller’s events MAY create or choose a set or pool of watchers. The validator chooses how the watchers are hosted. It MAY use a watcher service provided by some other party or MAY directly host its own watchers in its own infrastructure or some combination of the two. Nonetheless, the pool is under the ultimate control of the AID’s event validator. To clarify, it is not under the control of the AID’s controller. This means the validator MAY change its watcher infrastructure at will. Watchers are not AID-specific; instead, they watch the KELs of any or all AIDs that are shared with them. Watchers are not explicitly managed by key events. This is so that the watcher infrastructure used by any validator MAY be kept confidential and, therefore, unknown to potential attackers. It is up to each validator to manage its watcher infrastructure as it sees fit. Each validator uses its own watcher pool to watch the KELs of other controllers. When an AID has witnesses, the watchers of one validator watch the witnesses of the AID of some other controller. Each validator MAY use its own watcher pool to watch its own witness pool of the AID that it itself controls in order to detect external attacks on its witnesses.

Watchers MAY also exchange signed receipts of key events in the KELs they watch. Based on those receipts, a watcher pool could also employ the KAWA agreement algorithm to provide high availability, fault tolerance, and security guarantees. Thereby, a given validator’s watcher pool constitutes a highly available and secure confirmation network for any AIDs from other controllers it chooses to watch.

Watchers have a strong incentive to share all the KELs they watch. This is because Watchers follow a “first seen” policy (described in more detail below). Simply put, “first seen” means that only the first version of an event that a watcher receives is deemed by the watcher to be the one and only true version of the event. Any other versions received later are deemed invalid by that watcher, i.e., “first seen, always seen, never unseen.” Thus, any later compromise of the authoritative key state for the associated AID cannot produce an alternate version of the event that could supplant the first-seen version for a given watcher. Therefore, it is in the best interests of every honest AID controller to have its original version be accepted as first-seen as widely and as quickly as possible in order to nullify any future potential exploits against its key state. It is also in the best interest of every validator to have their own watchers “first see” the earliest version of all key events from all other controllers because those earliest events are, by design, the least likely to have been compromised. This strongly incentivizes both parties to support a widespread low-latency global network of watchers and watcher pools that share their first-seen KELs.

Watchers MAY implement different additional features. A watcher could choose to keep around any verifiable key events that differ from their first-seen version. These variants are, by nature, duplicitous; in order to be verifiable, a duplicitous variant MUST be properly fully signed and witnessed. The only way that two versions of a given event can be fully signed and witnessed is if the keys of the event’s controller have been compromised by an attacker or the controller itself acted duplicitously. The two cases could be indistinguishable to a watcher. However, both exhibit provable duplicity with regard to the key state. A watcher who records and provides such evidence of duplicity to other watchers is called a Juror. A Juror MAY be a member of a highly available, fault-tolerant pool of Jurors, called a Jury. A watcher who evaluates key events based on the evidence of duplicity or lack thereof as provided by one or more Juries is called a Judge. KERI thus enables the duplicity-evident exchange of data.

Ultimately, a validator decides whether or not to trust the key state of a given AID based on the evidence or lack thereof of duplicity. A given validator MAY choose to use Judge and Jury services to aid it in deciding whether or not to trust the key state of a given AID. An honest validator MUST trust when there is no evidence of duplicity and MUST NOT trust when there is any evidence of duplicity unless and until the duplicity has been reconciled. KERI provides mechanisms for duplicity reconciliation. These include key compromise recovery mechanisms.

Figure: Indirect Exchange

§ Ecosystem

The KERI protocol fosters an open, competitive ecosystem of service providers for the various infrastructure components such as controller applications (wallets, key chains, and agents), witnesses, and watchers (judges and juries). Because there is no requirement for shared governance over any of the infrastructure components, each controller and each validator is free to choose its own service providers based on price, performance, usability, etc. This enables competition across the full spectrum of infrastructure components. Thus, existing cloud and web infrastructure can be leveraged at comparable performance and price levels. KERI fosters the development of a global watcher network that will eventually result in universal duplicity detectability and ambient verifiability with the goal of providing a universal DKMI in support of a trust-spanning layer for the internet.

Figure: KERI Ecosystem

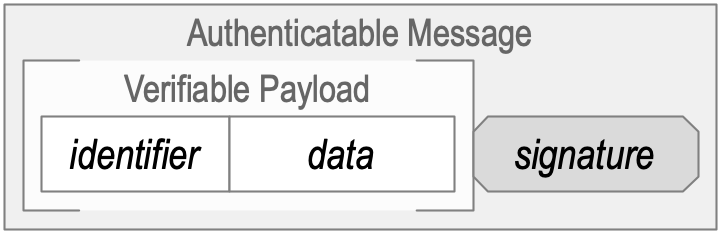

§ KERI’s identifier system security overlay

The function of KERI’s identifier-system security overlay is to establish the authenticity of the message payload in an IP Packet by verifiably attributing it to a cryptonymous SCID (an AID) via an attached set of one or more asymmetric keypair-based non-repudiable digital signatures. The current valid set of associated asymmetric keypair(s) is proven via a Verifiable data structure called the KEL. The identifier system provides a mapping between the identifier and the keypair(s) that control the identifier, namely, the public key(s) from those keypairs. The private key(s) is secret and is not shared.

An authenticatable (Verifiable) internet message (packet) or data item includes the identifier and data in its payload. Attached to the payload is a digital signature(s) made with the private key(s) from the controlling keypair(s). Given the identifier in a Message, any Verifier of a Message (data item) can use the identifier system mapping to look up the public key(s) belonging to the controlling keypair(s). The Verifier can then verify the attached signature(s) using that public key(s). Because the payload includes the identifier, the signature makes a non-repudiable cryptographic commitment to both the source identifier and the data in the payload.

Figure: Authenticatable Message

§ Overcoming existing security overlay flaws

KERI overcomes two major system security overlay flaws.

The first major flaw is that the mapping between the identifier (domain name) and the controlling keypair(s) is merely asserted by a trusted entity (a certificate authority or CA) via a certificate. Because the mapping is merely asserted, a Verifier cannot verify cryptographically the mapping between the identifier and the controlling keypair(s) but must trust the operational processes of the CA who issued and signed the certificate. As is well known, a successful attack upon those operational processes could fool a Verifier into trusting an invalid mapping — the certificate is issued to the wrong keypair(s) albeit with a Verifiable signature from a valid CA. Noteworthy is that the signature on the certificate is not made with the controlling keypairs of the identifier but made with keypairs controlled by the CA. The fact that the certificate is signed by the CA means that the mapping itself is not Verifiable but merely that the CA asserted the mapping between keypair(s) and identifier. The certificate merely provides evidence of the authenticity of the assignment of the mapping but not evidence of the veracity of the mapping.

The second major flaw is that when rotating the valid signing keys, there is no cryptographically Verifiable way to link the new (rotated in) controlling/signing key(s) to the prior (rotated out) controlling/signing key(s). Key rotation is asserted merely and implicitly by a trusted entity (CA) by issuing a new certificate with new controlling/signing keys. Key rotation is necessary because over time the controlling keypair(s) of an identifier becomes weak due to exposure when used to sign Messages and must be replaced. An explicit Rotation mechanism first revokes the old keys and then replaces them with new keys. Even a certificate revocation list (CRL) [[20]] as per [RFC5280], with an online status protocol (OCSP) registration as per [RFC6960], does not provide a cryptographically Verifiable connection between the old and new keys; This merely is asserted. The lack of a single universal CRL or registry means that multiple potential replacements could be valid. From a cryptographic verifiability perspective, Rotation by assertion with a new certificate that either implicitly or explicitly provides revocation and replacement is essentially the same as starting over by creating a brand-new independent mapping between a given identifier and the controlling keypair(s). This start-over style of Key rotation could well be one of the main reasons that other key assignment methods, such as Pretty Good Privacy (PGP’s) web-of-trust failed. Without a universally Verifiable revocation mechanism, any Rotation (revocation and replacement) assertion by some certificate authority, either explicit or implicit, is mutually independent of any other. This lack of universal cryptographic verifiability of a Rotation fosters ambiguity as to the actual valid mapping at any point in time between the identifier and its controlling keypair(s). In other words, for a given identifier, any or all assertions made by some set of CAs could be potentially valid.

The KERI protocol fixes both of these flaws using a combination of AIDs, key pre-rotation, and a Verifiable data structure, the KEL, as verifiable proof of Key state and duplicity-evident mechanisms for evaluating and reconciling Key state by Validators. Unlike certificate transparency, KERI enables the detection of Duplicity in the Key state via non-repudiable cryptographic proofs of Duplicity, not merely the detection of inconsistency in the Key state that MAY or MAY NOT be duplicitous.

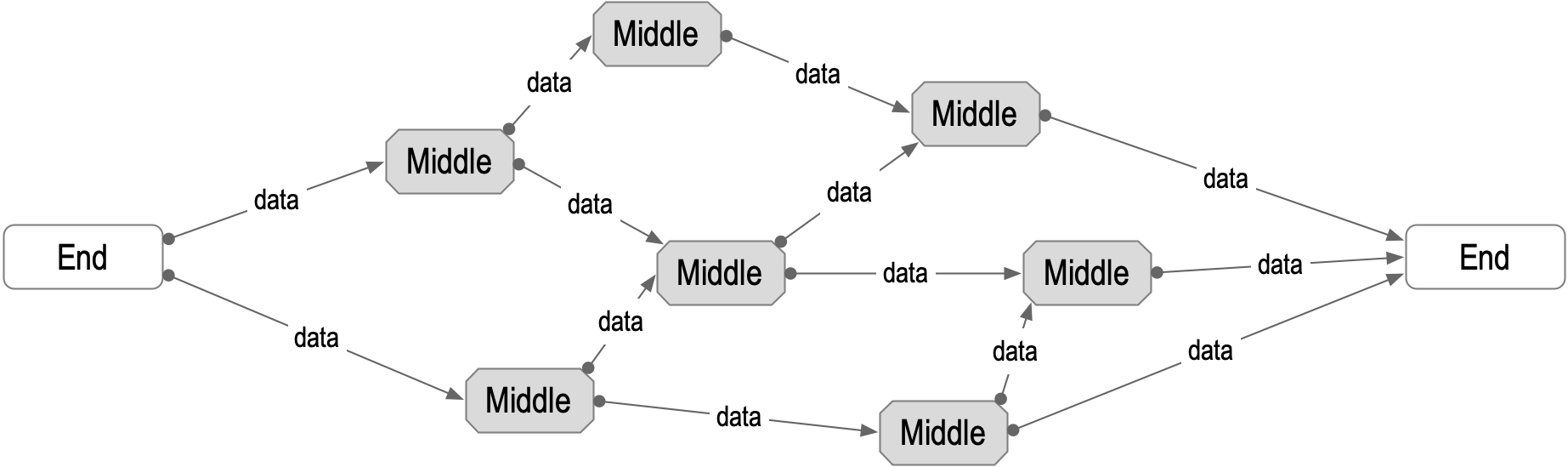

§ End-verifiable

A data item or statement is end-to-end-verifiable, or end-verifiable for short, when that data item could be cryptographically securely attributable to its source (party at the source end) by any recipient verifier (party at the destination end) without reliance on any infrastructure not under the verifier’s ultimate control. KERI’s end-verifiability is pervasive. It means that everything in KERI or that depends on KERI is also end-verifiable; therefore, KERI has no security dependency on any other infrastructure, including conventional PKI. It also does not rely on security guarantees that may or may not be provided by web or internet infrastructure. KERI’s identifier system-based security overlay for the Internet provides each identifier with a primary root-of-trust based on self-certifying, self-administering, self-governing AIDS and ANs that provides the trust basis for a universal AIS [[4]] [[16]] [[18]] [[19]] [[17]]. This root-of-trust is cryptographic, i.e. not administrative, because it does not rely on any trusted third-party administrative process but is established with cryptographically verifiable data structures alone.

Often, the two ends cannot transmit data directly between each other but relay that data through other components or infrastructure not under the control of either end. For example, Internet infrastructure is public and is not controlled by either end of a transmission. A term for any set of components that relays data between the ends or, equivalently, the party that controls it is the middle. The following diagram shows two ends communicating over the middle.

Figure: End-to-end Verifiability

End verifiability means that the end destination can verify the source of the data without having to trust the middle. This gives rise to the concept called ambient verifiability, where the source of any data can be verified anywhere, at any time, by anybody. Ambient verifiability removes any need to trust any of the components in the middle, i.e., the whole internet.

Another term for a party at one end of a transmission over a network (internet) is a network edge. End-verifiability of data means that if the edges of the network are secure, then the security of the middle does not matter. With KERI, the security of the edges is based primarily on the security of the key management at the edges. Therefore, a KERI-based system benefits greatly because protecting one’s private keys is much easier than protecting all internet infrastructure.

True end-verifiability means that only non-repudiable digital signatures based on asymmetric, i.e., public key cryptography, can be used to securely attribute data to a cryptographically derived source identifier, i.e., AID. In this sense, data is authentic with respect to its source identifier when it is verifiably nonrepudiably signed with the authoritative keypairs for that identifier at the time of signing. The result is that KERI takes a signed-everything approach to data both in motion and at rest. This enables a no-shared-secret approach to primary authentication, i.e., the primary authenticity of a data item is not reliant on the sharing of secrets between the source and recipient of any data item. Common types of shared secrets used for authentication include passwords, bearer tokens, and shared encryption keys, which are all vulnerable to exploitation. The result of a no-shared-secret sign-everything approach is the strongest possible authenticity, which means secure attribution to an AID.

End verifiability implies that the infrastructure needed to verify MUST be under the ultimate control of the verifier. Otherwise, the verifier must trust in infrastructure it does not control and, therefore, can’t fully verify. Thus end-verifiability is a prerequisite for true zero-trust computing infrastructure, where zero-trust means never trust always verify. The infrastructure in KERI is therefore split into two parts, the infrastructure controlled by the securely attributable source of any information where that source is identified by its AID. The source is, therefore, the AID controller. The AID controller’s infrastructure is its promulgation infrastructure. The output of the promulgation infrastructure is duplicity evident in cryptographically verifiable data structures that the verifier MAY verify. The verifier MAY employ its own infrastructure to aid it in both performing cryptographic verification and detecting duplicity. The verifier’s infrastructure is its confirmation infrastructure. This bifurcated architecture over verifiable data is more succinctly characterized as shared data but no shared governance. This naturally supports a no-shared-secret approach to authentication. Shared governance also usually comes with security, portability, cost, and performance limitations, which limit its more universal adoptability.

§ Self-certifying identifier (SCID)

The KERI identifier system overlay leverages the properties of cryptonymous SCIDs which are based on asymmetric PKI to provide end-verifiable secure attribution of any message or data item without needing to trust in any intermediary. A SCID is uniquely cryptographically derived from the public key of an asymmetric keypair, (public, private). The identifier is self-certifying in the sense that it does not rely on a trusted entity. Any non-repudiable signature made with the private key could be verified by extracting the public key from either the identifier itself or incepting information uniquely associated with the cryptographic derivation process for the identifier. In a basic SCID, the mapping between an identifier and its controlling public key is self-contained in the identifier itself. A basic SCID is ephemeral i.e., it does not support Rotation of its keypairs in the event of key weakness or compromise and therefore MUST be abandoned once the controlling private key becomes weakened or compromised from exposure. The class of identifiers that generalize SCIDs with enhanced properties such as persistence is called AIDs.

§ Autonomic identifier (AID)

The use of a KEL gives rise to an enhanced class of SCIDs that are persistent, i.e. not ephemeral, because the SCID‘s keys could be refreshed or updated via Rotation, allowing secure control over the identifier in spite of key weakness or even compromise. Members of this family of generalized enhanced SCIDs are called AIDs. Autonomic means self-governing, self-regulating, or self-managing and is evocative of the self-certifying, self-managing, and self-administering properties of this class of identifier. An AID could exhibit other self-managing properties, such as transferable control using key pre-rotation, which enables control over such an AID to persist in spite of key weakness or compromise due to exposure. Authoritative control over the identifier persists in spite of the evolution of the Key state.

§ Key rotation/pre-rotation

An important innovation of KERI is that it solves the key Rotation problem of PKI (including that of simple SCIDs) via a novel but elegant mechanism called key pre-rotation. This pre-rotation mechanism enables an entity to persistently maintain or regain control over an identifier in spite of the exposure-related weakening over time or even compromise of the current set of controlling (signing) keypairs. With key pre-rotation, control over the identifier can be re-established by rotating to a one-time use set of unexposed but pre-committed rotation keypairs that then become the current signing keypairs. Each Rotation, in turn, cryptographically commits to a new set of rotation keys but without exposing them. Because the pre-rotated keypairs need never be exposed prior to their one-time use, their attack surface could be optimally minimized. The current Key state is maintained via a KEL, an append-only Verifiable data structure. Cryptographic verifiability of the Key state over time is essential to remove this ambiguity over the mapping between the identifier (domain name) and the controlling keypair(s). Without this verifiability, the detection of potential ambiguity requires yet another bolt-on security overlay, such as the certificate transparency system.

§ Qualified Cryptographic Primitives

A Cryptographic primitive is a serialization of a value associated with a cryptographic operation, including but not limited to a digest (hash), a salt, a seed, a private key, a public key, or a signature. Furthermore, a Qualified cryptographic primitive includes a prepended derivation code (as a proem) that indicates the cryptographic algorithm or suite used for that derivation. This simplifies and compactifies the essential information needed to use that Cryptographic primitive. All Cryptographic primitives in KERI MUST be expressed using the CESR (Compact Event Streaming Representation) protocol [[1]]. A property of CESR is that all cryptographic primitives expressed in either its Text or Binary domains are qualified by construction. Indeed, cryptographic primitive qualification is an essential property of CESR which makes a uniquely beneficial encoding for a cryptographic primitive heavy protocol like KERI.

§ CESR Encoding

As stated previously, KERI represents all cryptographic primitives with [[1]]. CESR supports round-trip lossless conversion between its Text, Binary, and Raw domain representations and lossless composability between its Text and Binary domain representations. Composability is ensured between any concatenated group of text Primitives and the binary equivalent of that group because all CESR Primitives are aligned on 24-bit boundaries. Both the text and binary domain representations are serializations suitable for transmission over the wire. The Text domain representation is also suitable to be embedded as a field or array element string value as part of a field map serialization such as JSON, CBOR, or MsgPack. The Text domain uses the set of characters from the URL-safe variant of Base64, which in turn is a subset of the ASCII character set. For the sake of readability, all examples in this specification are expressed in CESR’s Text domain.

The CESR protocol supports several different types of encoding tables for different types of derivation codes used to qualify primitives. These tables include very compact codes. For example, a 256-bit (32-byte) digest using the BLAKE3 digest algorithm, i.e., Blake3-256, when expressed in Text domain CESR, consists of 44 Base64 characters that begin with the one-character derivation code E, such as EL1L56LyoKrIofnn0oPChS4EyzMHEEk75INJohDS_Bug. The equivalent qualified Binary domain representation consists of 33 bytes. Unless otherwise indicated, all Cryptographic primitives used in this specification are qualified Primitives expressed in CESR’s Text domain. This includes serializations that are signed, hashed, or encrypted.

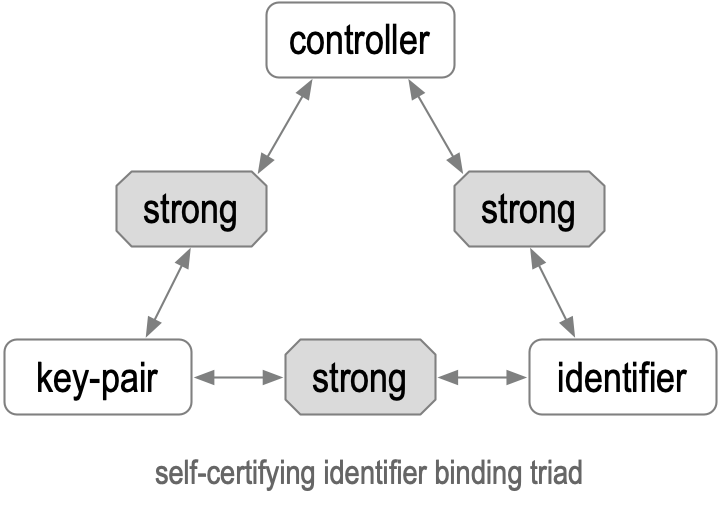

§ KERI’s secure bindings

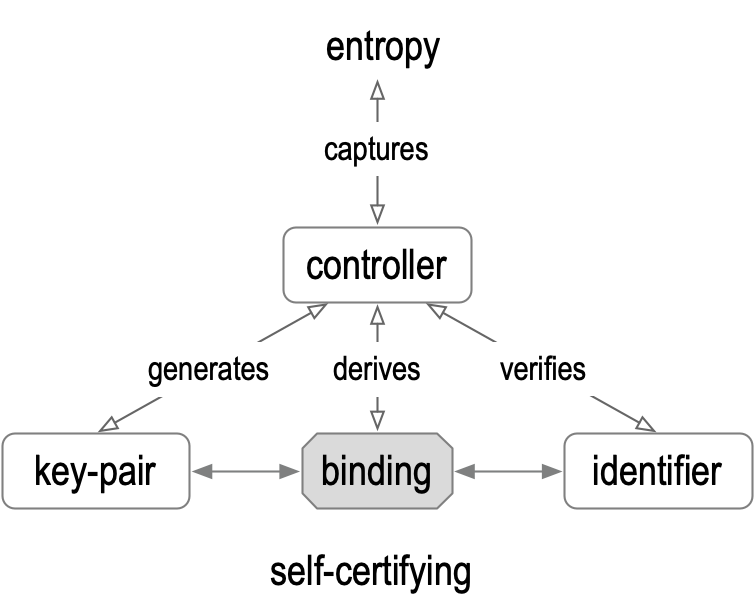

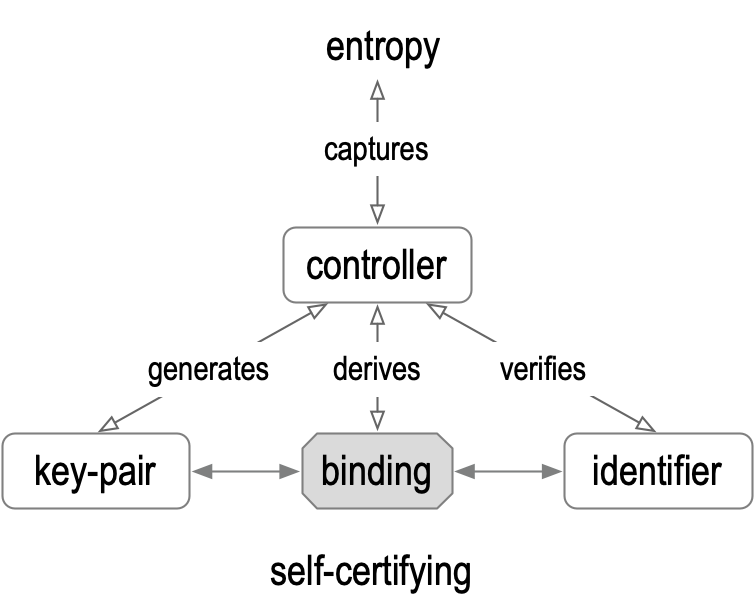

In simple form, an identifier-system security overlay binds together a triad consisting of the identifier, keypairs, and Controllers, the set of entities whose members control a private key from the given set of keypairs. The set of Controllers is bound to the set of keypairs, the set of keypairs is bound to the identifier, and the identifier is bound to the set of Controllers. This binding triad can be diagrammed as a triangle where the sides are the bindings and the vertices are the identifier, the set of Controllers, and the set of key pairs. This triad provides verifiable control authority for the identifier.

Figure: Self-certifying Identifier Binding Triad

When these bindings are strong, then the overlay is highly invulnerable to attack. In contrast, when these bindings are weak, then the overlay is highly vulnerable to attack. With KERI, all the bindings of the triad are strong because they are cryptographically Verifiable with a minimum cryptographic strength or level of approximately 128 bits. See Annex A on cryptographic strength for more detail.

The bound triad is created as follows:

Figure: Self-certifying Issuance Triad

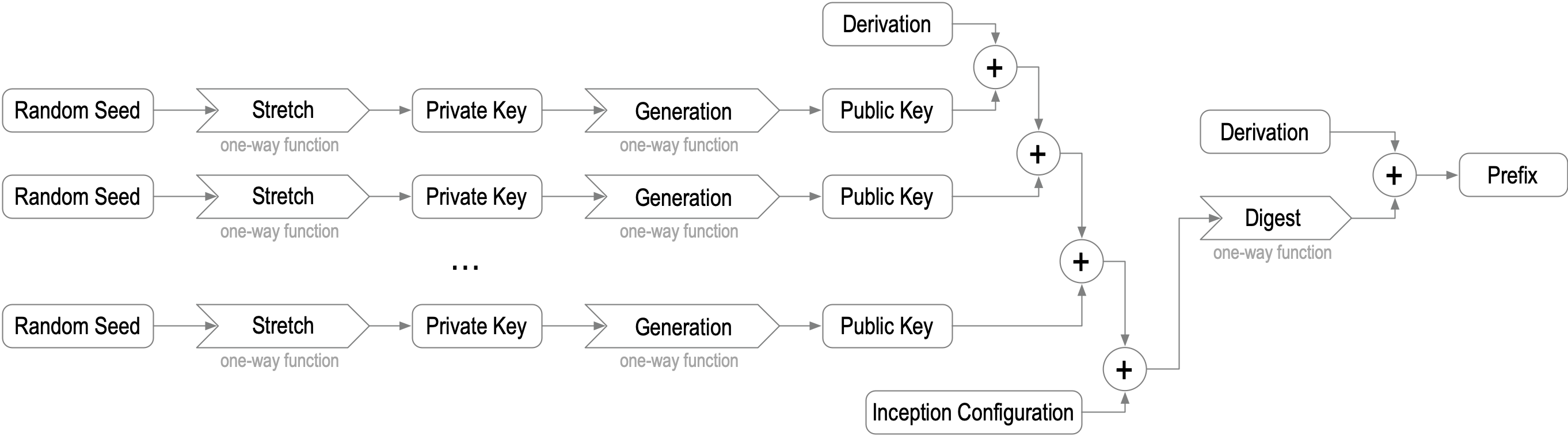

Each Controller in the set of Controllers creates an asymmetric (public, private) keypair. The public key is derived from the private key or seed using a one-way derivation that MUST have a minimum cryptographic strength of approximately 128 bits (nominally). Depending on the crypto-suite used to derive a keypair, the private key or seed could itself have a length larger than 128 bits. A Controller could use a cryptographic strength pseudo-random number generator (CSPRNG) to create the private key or seed material.

Because the private key material MUST be kept secret (by definition), typically in a secure data store, the management of those secrets could be an important consideration. One approach to minimize the size of secrets is to create private keys or seeds from a secret salt. The salt must have an entropy of approximately 128 bits. Then, the salt could be stretched to meet the length requirements for the crypto suite’s private key size. In addition, a hierarchical deterministic derivation function could be used to further minimize storage requirements by leveraging a single salt for a set or sequence of private keys.

Because each Controller is the only entity in control (custody) of the private key, and the public key is universally uniquely derived from the private key using a cryptographic strength one-way function, then the binding between each Controller and their keypair is as strong as the ability of the Controller to keep that key private. The degree of protection is up to each Controller to determine. For example, a Controller could choose to store their private key in a safe at the bottom of a coal mine, air-gapped from any network, with an ex-special forces team of guards. Or the Controller could choose to store it in an encrypted data store (key chain) on a secure boot mobile device with a biometric lock or simply write it on a piece of paper and store it in a safe place. The important point is that the strength of the binding between the Controller and keypair does not need to be dependent on any trusted entity.

The identifier is derived universally and uniquely from the set of public keys using a one-way derivation function. It is, therefore, an AID (qualified SCID). Associated with each identifier (AID) is incepting information that MUST include a list of the set of qualified public keys from the controlling keypairs. In the usual case, the identifier is a qualified cryptographic digest of the serialization of all the incepting information for the identifier. Any change to even one bit of the incepting information changes the digest and hence changes the derived identifier. This includes any change to any one of the qualified public keys, including its qualifying derivation code. To clarify, a qualified digest as an identifier includes a derivation code as a proem that indicates the cryptographic algorithm used for the digest. Thus, a different digest algorithm results in a different identifier. In this usual case, the identifier is bound strongly and cryptographically to the public keys and any other incepting information from which the digest was generated.

Figure: AID Identifier Prefix Derivation

A special case could arise when the set of public keys has only one member, i.e., there is only one controlling keypair. In this case, the Controller of the identifier could choose to use only the qualified public key as the identifier instead of a qualified digest of the incepting information. In this case, the identifier is still strongly bound to the public key but not to any other incepting information. A variant of this single keypair special case is an identifier that cannot be rotated. Another way of describing an identifier that cannot be rotated is that it is a non-transferable identifier because control over the identifier cannot be transferred to a different set of controlling keypairs. In contrast, a rotatable keypair is transferable because control can be transferred via rotation to a new set of keypairs. Essentially, when non-transferable, the identifier’s lifespan is ephemeral, not persistent, because any weakening or compromise of the controlling keypair means that the identifier MUST be abandoned. Nonetheless, there are important use cases for an ephemeral AID. In all cases, the derivation code in the identifier indicates the type of identifier, whether it be a digest of the incepting information (multiple or single keypair) or a single member special case derived from only the public key (both ephemeral or persistent).

Each Controller in a set of Controllers can prove its contribution to the control authority over the identifier in either an interactive or non-interactive fashion. One form of interactive proof is to satisfy a challenge of that control. The challenger creates a unique challenge Message. The Controller responds by nonrepudiably signing that challenge with the private key from the keypair under its control. The challenger can then cryptographically verify the signature using the public key from the Controller’s keypair. One form of non-interactive proof is the periodic contribution to a monotonically increasing sequence of nonrepudiably signed updates of some data item. Each update includes a monotonically increasing sequence number or date-time stamp. Any Verifier then can cryptographically verify the signature using the public key from the Controller’s keypair and verify that the update was made by the Controller. In general, only members of the set of Controllers can create verifiable, nonrepudiable signatures using their keypairs. Consequently, the identifier is strongly bound to the set of Controllers via provable control over the keypairs.

Figure: Self-certifying Identifier Issuance Triad

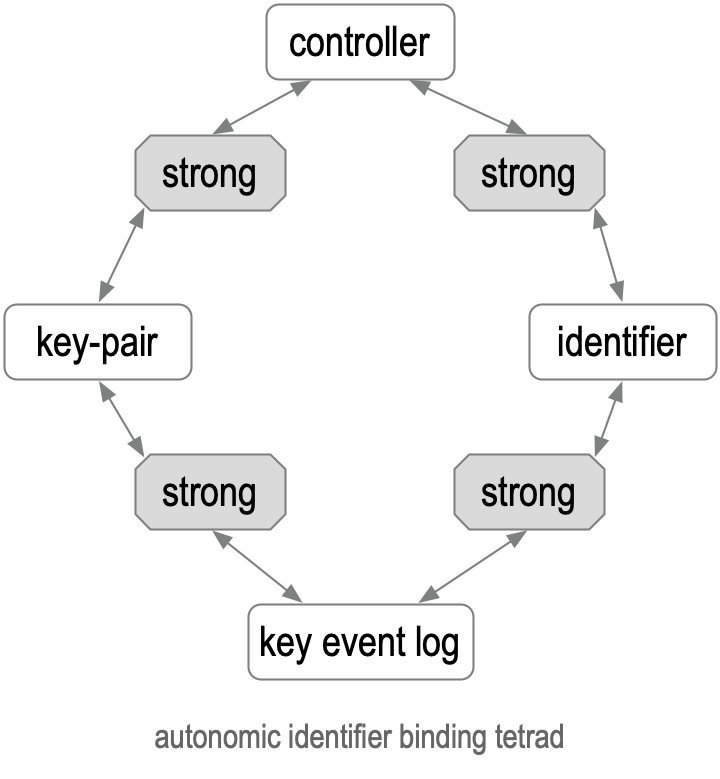

§ Tetrad bindings

At Inception, the triad of an identifier, a set of keypairs, and a set of Controllers are strongly bound together. But in order for those bindings to persist after a key Rotation, another mechanism is required. That mechanism is the KEL, a Verifiable data structure [[4]] [[21]]. The KEL is not necessary for non-transferable identifiers that do not need to persist control via key Rotation despite key weakness or compromise. To reiterate, transferable (persistent) identifiers each need a KEL; non-transferable (ephemeral) identifiers do not.

For persistent (transferable) identifiers, this additional mechanism can be bound to the triad to form a tetrad consisting of the KEL, the identifier, the set of keypairs, and the set of Controllers. The first entry in the KEL is called the Inception event, a serialization of the incepting information associated with the previously mentioned identifier.

Figure: Autonomic Identifier Binding Tetrad

The Inception event MUST include the list of controlling public keys and a signature threshold and be signed by a set of private keys from the controlling keypairs that satisfy that threshold. Additionally, for transferability (persistence across Rotation), the Inception event MUST include a list of digests of the set of pre-rotated public keys and a pre-rotated signature threshold that will become the controlling (signing) set of key keypairs and threshold after a Rotation. A non-transferable identifier MAY have a trivial KEL that only includes an Inception event but with a null set (empty list) of pre-rotated public keys.

A Rotation is performed by appending a Rotation event to the KEL. A Rotation event MUST include a list of the set of pre-rotated public keys (not their digests), thereby exposing them, and be signed by a set of private keys from these newly exposed newly controlling but pre-rotated keypairs that satisfy the pre-rotated threshold. The Rotation event MUST include a list of the digests of a new set of pre-rotated keys as well as the signature threshold for the set of pre-rotated keypairs. At any point in time, the transferability of an identifier MAY be removed via a Rotation event that rotates to a null set (empty list) of pre-rotated public keys. Rotating to a null set of pre-rotated public keys signals to any verifier that the controller has abandoned the identifier.

Each event in a KEL MUST include an integer sequence number that is one greater than the previous event. Each event after the Inception event also MUST include a cryptographic digest of the previous event. This digest means that a given event is bound cryptographically to the previous event in the sequence. The list of digests or pre-rotated keys in the Inception event cryptographically binds the Inception event to a subsequent Rotation event, essentially making a forward commitment that forward chains together the events. The only valid Rotation event that MAY follow the Inception event MUST include the pre-rotated keys. But only the Controller who created those keys and created the digests can verifiably expose them. Each Rotation event, in turn, makes a forward commitment (chain) to the following Rotation event via its list of pre-rotated key digests. This makes the KEL a doubly (backward and forward) hash (digest) chained nonrepudiably signed append-only Verifiable data structure.

Because the signatures on each event are nonrepudiable, the existence of an alternate but Verifiable KEL for an identifier is provable evidence of Duplicity. In KERI, there MUST be at most one valid KEL for any identifier or none at all. Any Validator of a KEL can enforce this one valid KEL rule that protects the Validator before relying on the KEL as proof of the current key state for the identifier. Any unreconcilable evidence of Duplicity means the Validator does not trust (rely on) any KEL to provide the key state for the identifier. Rules for handling reconcilable Duplicity will be discussed below in section Reconciliation. From a Validator’s perspective, either there is one-and-only-one valid KEL or none at all, which also protects the Validator by removing any potential ambiguity about the Key state. The combination of a Verifiable KEL made from nonrepudiably signed backward and forward hash chained events together with the only-one-valid KEL rule strongly binds the identifier to its current Key state as given by that one valid KEL (or not at all). This, in turn, binds the identifier to the Controllers of the current keypairs given by the KEL, thus completing the tetrad.

At Inception, the KEL can be bound even more strongly to its tetrad by deriving the identifier from a digest of the Inception event so that even one change in any of the incepting information included in the Inception event will result in a different identifier (including not only the original controlling keys pairs but also the pre-rotated keypairs).

The essence of the KERI protocol is a strongly bound tetrad of an identifier, set of keypairs, set if Controllers, and the KEL that forms the basis of its identifier system security overlay. The KERI protocol introduces the concept of Duplicity evident programming via Duplicity evident Verifiable data structures.

Figure: Autonomic Identifier Issuance Tetrad

§ Autonomic Namespaces (ANs)

A namespace groups symbols or identifiers for a set of related objects [[23]]. In an identity system, an identifier can be generalized as belonging to a namespace that provides a systematic way of organizing related identifiers with their resources and attributes.

To elaborate, a namespace employs some scheme for assigning identifiers to the elements of the namespace. A simple name-spacing scheme uses a prefix or prefixes in a hierarchical fashion to compose identifiers. The following is an example of a namespace scheme for addresses within the USA that uses a hierarchy of prefixes:

state.county.city.zip.street.number.

An example element in this namespace could be identified with the following:

utah.wasatch.heber.84032.main.150S.

where each prefix location has been replaced with the actual value of the element of the address. Namespaces provide a systematic way of organizing related elements and are widely used in computing.

An autonomic namespace, AN, is defined as a namespace with an AID as a prefix, i.e., a fully qualified CESR-encoded cryptographic primitive. As defined above, AIDs are uniquely (strongly) cryptographically bound to their incepting controlling keypair(s) at issuance. They are, hence, self-certifying. In addition, AIDs are also bound to other key management information, such as the hashes of the next pre-rotated rotation keys and their witnesses. This makes them self-managing.

To clarify, each identifier from an AN includes as a prefix an identifier encoded in CESR that either is the public key or is uniquely cryptographically derived from the public key(s) of the incepting (public, private) key pair. The controller can then use the associated private key(s) to authoritatively (nonrepudiably) sign statements that authenticate and authorize the use of the identifier. These statements include responses to challenges to prove control over the identifier. Thus, self-certification enables both self-authentication and self-authorization capabilities as well as self-management of cryptographic signing keypairs. Together, these properties make the namespace self-administering.

To restate, An AN is self-administrating. The self-administering properties of an AN mean that the resources identified by that namespace can also be governed by the controller of the key pair(s) that are authoritative for its AID prefix. Essentially, a namespace of identifiers can be imbued with the secure attributability properties of an AID when used as its prefix. When secure attribution arises solely from the AID as the prefix, then the other elements in the namespace syntax are immaterial with respect to secure attribution. This makes the prefix agnostic about the syntax of any ANs in which it appears. The same AID can be used to control multiple disparate namespaces. This provides opportunities for AIDs to interoperate with many existing namespaces. The AID prefix from any autonomically namespaced identifier merely needs to be extracted to use the prefix with a KERI protocol library.

In general, a fully qualified AID primitive and an identifier from an AN based on that primitive as a prefix can both be referred to as AIDs with the understanding that any cryptographic operations only apply to the prefix portion of the namespaced identifier.

The primary purpose of an AID is to enable any entity to establish control over its associated identifier namespace in an independent, interoperable, and portable way. This approach builds on the idea of an identity (identifier) meta-system that enables interoperability between systems of identity (identifiers) that not only exposes a unified interface but adds decentralized control over their identifiers. This enables portability, not just interoperability. Given portability in an identity (identifier) meta-system system, transitive trust can occur, that is, the transfer of trust between contexts or domains. Because transitive trust facilitates the transfer of other types of value, a portable decentralized identity meta-system, e.g., an AID system, enables an identity meta-platform for commerce.

§ KERI data structures and labels

§ KERI data structure format

A KERI data structure, such as a Key event Message body, can be abstractly modeled as a nested key: value mapping. To avoid confusion with the cryptographic use of the term key, the term field is used instead herein to refer to a mapping pair, with the terms field label and field value used to refer to each pair member. Two tuples can represent these pairs, e.g., (label, value). When necessary, this terminology is qualified by using the term field map to reference such a mapping. Field maps can be nested where a given field value is itself a reference to another field map and are referred to as a nested field map or simply a nested map for short.

A field can be represented by a framing code or block delimited serialization. In a block delimited serialization, such as JSON, each field map is represented by an object block with block delimiters such as {}. Given this equivalence, the term block or nested block can be used as synonymous with field map or nested field map. In many programming languages, a field map is implemented as a dictionary or hash table. This enables performant asynchronous lookup of a field value from its field label. Reproducible serialization of field maps requires a canonical ordering of those fields. One such canonical ordering is called insertion or field creation order. A list of (field, value) pairs provides an ordered representation of any field map.

Most programming languages now support ordered dictionaries or ordered hash tables that provide reproducible iteration over a list of ordered field (label, value) pairs where the ordering is the insertion or field creation order. This enables reproducible round-trip serialization/deserialization of field maps. Serialized KERI data structures depend on insertion-ordered field maps for their canonical serialization/deserialization. KERI data structures support multiple serialization types, namely JSON, CBOR, MGPK, and CESR but for the sake of simplicity, JSON only will be used for examples. The basic set of normative field labels in KERI field maps is defined by the table below (see the next section).

§ KERI field labels for data structures

Reserved field labels in Keri messages:

| Label | Title | Description |

|---|---|---|

v |

Version String | enables regex parsing of field map in CESR stream |

t |

Message Type | three character string |

d |

Digest SAID | fully qualified digest of block in which it appears |

i |

Identifier Prefix (AID) | fully qualified primitive, Controller AID |

s |

Sequence Number | strictly monotonically increasing integer encoded in hex |

p |

Prior SAID | fully qualified digest, prior message SAID |

kt |

Keys Signing Threshold | hex encoded integer or fractional weight list |

k |

List of Signing Keys (ordered key set) | list of fully qualified primitives |

nt |

Next Keys Signing Threshold | hex encoded integer or fractional weight list |

n |

List of Next Key Digests (ordered key digest set) | list of fully qualified primitives digests |

bt |

Backer Threshold | hex encoded integer |

b |

List of Backers (ordered backer set of AIDs) | list of fully qualified primitives |

br |

List of Backers to Remove (ordered backer set of AIDS) | list of fully qualified primitives |

ba |

List of Backers to Add (ordered backer set of AIDs) | list of fully qualified primitives |

c |

List of Configuration Traits/Modes | list of strings |

a |

List of Anchors (seals) | list of field maps |

di |

Delegator Identifier Prefix (AID) | fully qualified primitive, Delegator AID |

A field label MAY have different values in different contexts but MUST NOT have a different field value type. This REQUIREMENT makes it easier to implement in strongly typed languages with rigid data structures. Notwithstanding the former, some field value types MAY be a union of elemental value types.

Because the order of field appearance MUST be enforced in all KERI data structures, whenever a field appears (in a given Message or block in a Message), the message in which a label appears MUST provide the necessary context to determine the meaning of that field fully and hence the field value type and associated semantics.

§ Compact KERI field labels

The primary field labels are compact in that they use only one or two characters. KERI is meant to support resource-constrained applications such as supply chain or IoT (Internet of Things) applications. Compact labels better support resource-constrained applications in general. With compact labels, the over-the-wire verifiable signed serialization consumes a minimum amount of bandwidth. Nevertheless, without loss of generality, a one-to-one normative semantic overlay using more verbose expressive field labels can be applied to the normative compact labels after verification of the over-the-wire serialization. This approach better supports bandwidth and storage constraints on transmission while not precluding any later semantic post-processing. This is a well-known design pattern for resource-constrained applications.

§ Special label ordering requirements

The top-level fields of each message type MUST appear in a specific order. All top-level fields are REQUIRED. This enables compact top-level fixed field CESR native messages. These top-level fields are defined for each message type below.

§ Version string field

The version string, v, field MUST be the first field in any top-level KERI field map encoded in JSON, CBOR, or MGPK as a message body [RFC4627] [RFC4627] [[2]] RFC8949 [[3]]. It provides a regular expression target for determining a serialized field map’s serialization format and size (character count) constituting an KERI message body. A stream parser can use the version string to extract and deserialize (deterministically) any serialized stream of KERI message bodies. Each KERI message body in a stream MAY use a different serialization type. The format for the version string field value is defined in the CESR specification [[1]].

The protocol field, PPPP value in the version string MUST be KERI for the KERI protocol. The version field, VVV, MUST encode the current version of the KERI protocol [[1]].

§ Legacy version string field format

Compliant KERI version 2.XX implementations MUST support the old KERI version 1.x version string format to properly verify message bodies created with 1.x format events. The old version 1.x version string format is defined in the CESR specification [[1]]. The protocol field, PPPP value in the version string MUST be KERI for the KERI protocol. The version field, vv, MUST encode the old version of the KERI protocol [[1]].

§ Message type field

The message type, t field value MUST be a three-character string that provides the message type. There are three classes of message types in KERI. The first class consists of key event messages. These are part of the KEL for an AID. A subclass of key event messages are Establishment Event messages, these determine the current key state. Non-establishment event messages are key event messages that do not change the key state. The second class of messages consists of Receipt messages. These are not themselves part of a KEL but convey proofs such as signatures or seals as attachments to a key event. The third class of messages consists of various message types not part of a KEL but are useful for managing the information associated with an AID.

The message types in KERI are detailed in the table below:

| Type | Title | Class | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key Event Messages | |||

icp |

Inception | Establishment Key Event | Incepts an AID and initializes its keystate |

rot |

Rotation | Establishment Key Event | Rotates the AID’s key state |

ixn |

Interaction | Non-Establishment Key Event | Seals interaction data to the current key state |

dip |

Delegated Inception | Establishment Event | Incepts a Delegated AID and initializes its keystate |

drt |

Delegated Rotation | Establishment Key Event | Rotates the Delegated AID’s key state |

| Receipt Messages | |||

rct |

Receipt | Receipt Message | Associates a proof such as signature or seal to a key event |

| Routed Messages | |||

qry |

Query | Other Message | Query information associated with an AID |

rpy |

Reply | Other Message | Reply with information associated with an AID either solicited by Query or unsolicited |

pro |

Prod | Other Message | Prod (request) information associated with a Seal |

bar |

Bare | Other Event | Bare (response) with information associated with a Seal either solicited by Prod or unsolicited |

xip |

Exchange Inception | Other Message | Incepts multi-exchange message transaction, the first exchange message in a transaction set |

exn |

Exchange | Other Message | Generic exchange of information, MAY be a member of a multi-message transaction set |

§ SAID fields

Some fields in KERI data structures can have a SAID (self-referential content addressable), as a field value. In this context, d is short for digest, which is short for SAID. A SAID follows the SAID protocol. A SAID is a special type of cryptographic digest of its encapsulating field map (block). The encapsulating block of a SAID is called a SAD (Self-Addressed Data). Using a SAID as a field value enables a more compact but secure representation of the associated block (SAD) from which the SAID is derived. Any nested field map that includes a SAID field (i.e., is, therefore, a SAD) MAY be compacted into its SAID. The uncompacted blocks for each associated SAID MAY be attached or cached to optimize bandwidth and availability without decreasing security.

Each SAID provides a stable universal cryptographically verifiable and agile reference to its encapsulating block (serialized field map).

A cryptographic commitment (such as a digital signature or cryptographic digest) on a given digest with sufficient cryptographic strength including collision resistance is equivalent to a commitment to the block from which the given digest was derived. Specifically, a digital signature on a SAID makes a Verifiable cryptographic non-repudiable commitment that is equivalent to a commitment on the full serialization of the associated block from which the SAID was derived. This enables reasoning about KERI data structures in whole or in part via their SAIDS in a fully interoperable, Verifiable, compact, and secure manner. This also supports the well-known bow-tie model of Ricardian Contracts [[22]]. This includes reasoning about the whole KERI data structure given by its top-level SAID, d, field as well as reasoning about any nested or attached data structures using their SAIDS.

The SAID, d field is the SAID of its enclosing block (field map); when it appears at the top level of the message, it is the SAID of the message itself.

The prior, p field is the SAID of a prior event message. When the prior p field appears in a key event message, then its value MUST be the SAID of the key event message whose sequence number is one less than the sequence number of its own key event message. Only key event messages have sequence numbers. Routed messages do not. When the prior, p field appears in an Exchange, exn message then its value is the SAID of the prior exchange message in the associated exchange transaction.

§ AID fields

Some fields, such as the i and di fields, MUST each have an AID as its value. An AID is a fully qualified primitive as described above KERI [[4]].

In this context, i is short for ai, which is short for the Autonomic identifier (AID). The AID given by the i field can also be thought of as a securely attributable identifier, authoritative identifier, authenticatable identifier, authorizing identifier, or authoring identifier. Another way of thinking about an i field is that it is the identifier of the authoritative entity to which a statement can be securely attributed, thereby making the statement verifiably authentic via a non-repudiable signature made by that authoritative entity as the Controller of the private key(s).

The Controller AID, i field value is an AID that controls its associated KEL. When the Controller Identifier AID, i field appears at the top-level of a key event, [icp, rot, ixn, dip, drt] or a receipt, rct message it refers to the Controller of the associated KEL. When the Controller Identifier AID, i field appears at the top-level of an Exchange Transaction Inception, xip or Exchange, exn message it refers Controller AID of the sender of that message. A Controller AID, i field MAY appear in other places in messages. In those cases, its meaning SHOULD be determined by the context of its appearance.

The Delegator identifier AID, di field in a Delegated Inception, dip event is the AID of the Delegator.

§ Sequence number field

The Sequence Number, s field value is a hex encoded (no leading zeros) non-negative strictly monotonically increasing integer. The Sequence Number, s field value in Inceptions, icp and Delegated Inception, dip events MUST be 0 (hex encoded 0). The Sequence number value of all subsequent key events in a KEL MUST be 1 greater than the previous event. The maximum value of a sequence number MUST be ffffffffffffffffffffffffffffffff which is the hex encoding of `2^128 - 1 = 340282366920938463463374607431768211455’. This is large enough to be deemed computationally infeasible for a KEL ever to reach the maximum.

§ Key and key digest threshold fields

The Key Threshold, kt and Next Key Digest Threshold, nt field values each provide signing and rotation thresholds, respectively, for the key and next key digest lists. The threshold value MAY be either the simple case of a hex-encoded non-negative integer or the complex case of a list of clauses of fractional weights. The latter is called a fractionally weighted threshold.

In the simple case, given a threshold value M together with a total of N values in a key or key digest list, then the satisfaction threshold is an M of N threshold. This means that any set of M valid signatures from the keys in the list satisfies such a threshold.

In the complex case, the field value is a list of weights that are strict decimal-encoded rational fractions. Fractionally weight thresholds are best suited for Partial, Reserve, or Custodial rotation applications. The exact syntax and satisfaction properties of fractionally weighted threshold values are described below in the section on Partial, Reserve, and Custodial rotations.

§ Key list field

The Key, k field value is a list of strings that are each a fully qualified public key. These provide the current signing keys for the AID associated with a KEL. The Key, k field value MUST NOT be empty.

§ Next key digest list field

The Next Key Digest, n field value is a list of strings that are each a fully qualified digest of a public key. These provide the next rotation keys for the AID associated with a KEL. When the Next, n field value in an Inception or Delegated Inception event is an empty list, then the associated AID MUST be deemed non-transferable, and no more key events MUST be allowed in that KEL. When the Next, n field value in a Rotation or Delegated Rotation Event event is an empty list, then the associated AID MUST be deemed abandoned, and no more key events MUST be allowed in its KEL.

§ Backer threshold field